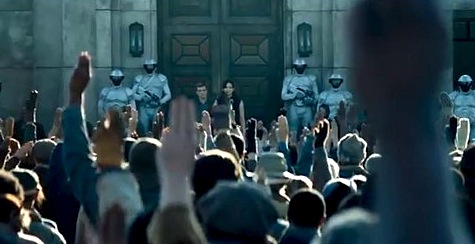

A military coup in Thailand has led many protestors to adopt the three-fingered salute from Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games series as a form of resistance to the current political state of their country. Of course, while oppression may be counted as a throughline in the situation, the specifics of the upheaval in Thailand is not solidly comparable to the dystopian future Collins created.

Instead, it is a reminder of how the symbols we find in fiction can affect our lives and the world around us.

To be clear on what is occurring: late last month, Thailand’s democratic government was overthrown in a military coup—the second coup that the country has gone through in less than a decade. The government was deposed, and General Prayuth Chan-ocha called for two days of peace talks between government officials. The talks lasted only four hours, and Prayuth announced via television that the army was seizing power. He warned the people not to protest.

But the people of Thailand are protesting and what’s more, they’ve chosen the symbol of Panem’s rebellion to communicate their dissent—a three-finger salute that District 12 offers Katniss Everdeen when she takes her sister’s place in the Games, a symbol that spreads and eventually becomes a signal in support of revolution against the Capitol. Protestors in Thailand are gathering in groups, sometimes just a few people at once, and silently showing their opposition to the new regime.

Jonathan Jones of The Guardian has not looked kindly on the matter, insisting that the adoption of this symbol indicates a lack of political understanding on the part of the current generation of young protesters:

In an age of torched ideologies and ruined utopias, the symbols of dissent have to be newly forged, recast out of what comes to hand. What comes easiest to hand is popular culture. But do The Hunger Games or V for Vendetta really offer useful images, or does this reliance on them reveal a tragic intellectual vacuum?

Images have meaning. The clenched fist of Marxist revolutionaries was not just a gesture. Behind it lay a history of revolution going back to 1789 and a huge body of serious political thought from The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte to the writings of Antonio Gramsci. But what does it actually mean to claim allegiance to The Hunger Games?

In essence, Jones believes that anyone who would look to pop culture narratives for appropriate political symbols is living the life of a philistine—that the gesture adopted by the people of Thailand has no history in real world political uprisings, and therefore no true meaning. He talks of the Hunger Games in terms of “teenagers’ sensibilities,” conveniently ignoring the fact that teenagers are being affected in Thailand as well, and also have the right to be heard. It’s paternalistic at best, and at worst completely dismissive of the actual risk these protestors are taking by making their dissent public. By all means, judge them for looking to a book for inspiration while you are safely tucked away in another country where these issues are not currently plaguing the political landscape.

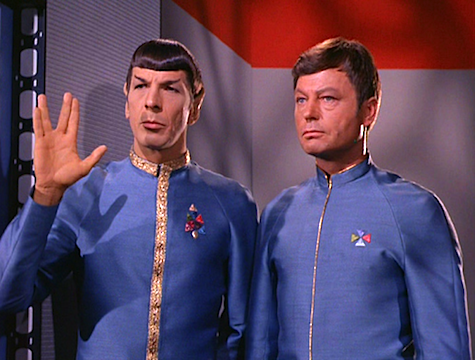

Symbols are changeable things. Fiction knows this better than Jones because fiction has been lifting and appropriating symbols forever. That three-finger salute used in The Hunger Games? The Scouts have been using it for decades. The salute Vulcans use on Star Trek while telling someone to “Live Long and Prosper” is actually a Jewish symbol that Leonard Nimoy picked out because he remembered learning it in his grandfather’s synagogue as a boy. Farscape’s Peacekeepers tack up banners emblazoned with famous Soviet propaganda art. We don’t typically criticize fiction for this—why would we criticize others for looking to fiction in return?

This is not a new trend either. Jones himself takes a jab at the Guy Fawkes mask being re-popularized by the V for Vendetta film, then commandeered as a symbol of rebellion by Occupy Wall Street and Anonymous. Now, say what you want about that movie and how it relates to Alan Moore’s original work—it is not difficult to understand why people might have found that narrative moving. Nor is it difficult to see what these movements actually mean by appropriating V’s mask; obviously, the individuals involved do not think they are living in the same world as those fictional characters. But they can see the places where a connection might be made, where the sentiments align. And by taking on that symbol, they are giving a clear signal to everyone who sees it. They are letting the world know how they feel about what is happening around them.

Guess that’s just not enough for some people. Because every political movement must communicate with symbols drawn from the politico-historical past only! Clearly the Great Plains Tar Sands Resistance group should have seen their folly when they used the Mockingjay as a symbol of protest against Devon Energy. They were arrested for their trouble, but since their choice of imagery lacks any real-world political connection, it’s just not meaningful or evocative enough to warrant our attention, right? And 1960s counterculture should have stopped spray painting “Frodo Lives” under bridges because Tolkien definitely did not approve of these layabout hippie kids aligning themselves with his work in that way.

Thing is, we do this all the time. Whether it’s jokes about President Obama being Spock, or calling a defense initiative “Star Wars” when we find it unrealistic, we are constantly linking the political and the fictional. There is nothing automatically bad or strange or vacuous about this impulse, and it doesn’t prove that we lack political savvy or have been deluded into thinking that our lives are actually similar to the Hunger Games. It means that when something moves us, and has meaning for us, we sometimes make it part of our identity. And we do that in tiny non-political ways as well; getting a tattoo of Superman’s “S,” wearing a Ravenclaw scarf, naming your cat Buffy the Mouse Slayer. Claiming that there is something inherently wrong about this is flat out denying what people do best. We see patterns, as a species. We like to make things connect.

That said, I hope that the protestors in Thailand stay safe and that their chosen symbol works well for them as they make their stand. If they’ve chosen it, it means something to them, and that should be enough for anyone.

Emmet Asher-Perrin is a staff writer at Tor.com. You can bug her on Twitter and read more of her work here and elsewhere.